Learning About The Physics of Ultrafast Lasers

What are Ultrafast Lasers

Based on the output waveform of energies, lasers can be classified into continuous lasers, pulsed lasers, and quasi-continuous lasers:

Continuous lasers: Lasers that continuously output a stable waveform of constant power during operation. The characteristic of continuous lasers is the accumulation of laser powers, enabling the processing of large-volume materials with high melting points, such as metal sheets.

Pulsed lasers: These lasers emit energy in pulse form. Based on pulse width, pulsed lasers can be further classified. For example, if a pulsed laser emits laser pulses with a pulse width between 1 and 1,000 ns, it is referred to as a nanosecond laser, and so on. Picosecond lasers, femtosecond lasers, and attosecond lasers are collectively referred to as ultrafast lasers. So, ultrafast lasers can be defined as pulsed lasers with pulse durations less than 1^-12 seconds.

Quasi-continuous lasers: These lasers fall between continuous lasers and pulsed lasers, capable of repeatedly emitting high-energy laser beams within a certain cycle. Theoretically, they are also a type of pulsed laser.

Ultrafast lasers are also referred to as “ultra-intense ultra-short pulse lasers” or “ultra-short pulse lasers,” but we prefer to call them “ultrafast lasers” because this definition is related to” ultrafast phenomena.” Ultrafast phenomena refer to phenomena occurring in rapid physical, chemical, or biological processes within microscopic material systems: in atomic and molecular systems, the timescale of atomic and molecular motion is approximately in the picosecond to femtosecond range, such as the rotational period of molecules being in the picosecond range and the vibrational period being in the femtosecond range; When the pulse width of a laser pulse reaches the picosecond or femtosecond range, it can largely avoid the influence of the overall thermal motion of molecules (molecular thermal motion is the microscopic essence of material temperature) and instead affect the material at the time scale of molecular vibrations. This allows the processing objective to be achieved while significantly reducing thermal effects.

In the field of material processing, pulsed lasers initially served as a transitional product to continuous lasers. This was due to limitations imposed by the capabilities of core components and manufacturing processes at the time, which prevented continuous lasers from achieving sufficiently high output power to heat materials above their melting points and thus achieve the desired processing results; However, by using certain technical methods to concentrate the laser's output energy into a single pulse, although the total power of the laser remains unchanged, the instantaneous power at the pulse generation point is significantly increased, thereby meeting the requirements of material processing. Later, as continuous laser technology matured, it was discovered that pulsed lasers have a significant advantage in processing precision. This is primarily because pulsed lasers have a smaller thermal effect on materials, and the narrower the laser pulse width, the smaller the thermal impact, resulting in smoother edges of the processed material (corresponding to higher processing precision).

You can also learn more about ultrafast laser mirrors here. or might be interested in Instant Guide-Important Specifications for Ultrafast Optics

Characteristics of Ultrafast Lasers-Spectral Bandwidth and Peak Power

Ultrafast lasers have two characteristics: one is broad spectral bandwidths, and one is extremely high peak power. A broad spectral range is essential for generating ultrafast lasers. This can be explained using the time-frequency uncertainty principle (Fourier transform limit). According to the Fourier transform, the shorter the duration of a laser pulse, the broader its spectral width in the frequency domain (i.e., the spectrum). The relationship between spectral bandwidth and pulse duration can be expressed mathematically as follows:

Δt*Δv≥ 4π/1

Where Δt is the pulse duration, and Δν is the spectral bandwidth. For example, a femtosecond laser with a pulse duration of 100fs will need a frequency bandwidth of around 10THz, which is a spectral bandwidth of dozens of nanometers.

This is because fundamentally, ultrafast pulsed lasers are obtained by the phase locking (i.e., superposition) of multiple components of frequencies. If you want to obtain a very narrow pulse width temporally, you have to introduce more components of frequencies, which means a wider wavelength range.

Another important characteristic of an ultrafast laser is its high power, which is due to its very short pulse duration. Let’s look at how we should calculate the peak power of a pulsed laser first. For a femtosecond laser with an average power of 1W, a repetition rate of 1 MHz, and a pulse width of 100 fs, the pulse energy of a single pulse is:

pulse energy=average power*time=1W/1x10^6Hz=1uJ

Then we can calculate the peak power:

peak power=pulse energy/pulse duration=1uJ/1x10^-15s=1x10^6W=1MW

As we can conclude, although the pulse energy of a single pulse is miniature (just 1uJ), as the pulse width gets very short, an enormous peak power can be obtained.

How Are Ultrafast Lasers Generated-Mode Locking and Chirped Pulse Amplification

Mode-locking:

Mode-locking: Mode locking means achieving phase synchronization (with a constant phase difference) of the longitudinal modes within the laser resonator to generate ultrashort pulsed lasers. Mode-locking technology can be generally divided into active mode-locking (by using electro-optic modulators) and passive mode-locking (by using saturable absorbers or SESAM).

The laser resonator supports multiple longitudinal modes (standing wave modes of different frequencies), which are discrete and evenly spaced in the frequency domain. When waves of multiple frequencies are in phase, they add together at certain moments to form sharp pulses, and cancel each other out at other times.

This “interference superposition” in the time domain results in pulses with extremely short durations and peak power. Mode locking is used to make multiple longitudinal modes superpose. The larger the number of the longitudinal modes, and the wider the intervals between frequencies, the shorter the pulse duration. The current mold locking pulse width can be as short as 5 femtoseconds. The peak power is in the gigawatt range.

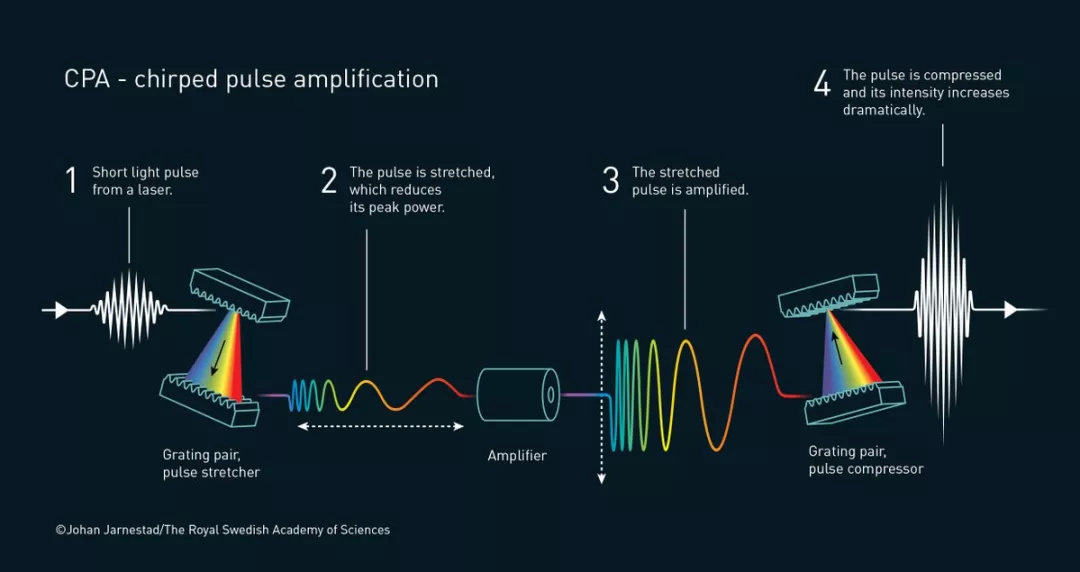

Chirped Pulse Amplification (CPA)

Before the advent of chirped pulse amplification technologies, scientists had already been able to use ultrafast laser techniques such as Q-switching and mode-locking to increase laser pulse durations from the millisecond (ms) range to the nanosecond (ns) and picosecond (ps) ranges. However, directly amplifying the energy of laser pulses to further increase peak power encountered an insurmountable bottleneck. This is because during direct amplification, the extremely high peak power density of laser pulses easily damages the gain medium and other transmissive optical components within the amplifier.

The emergence of chirped pulse amplification technology has addressed this issue. The basic principle of this technology is as follows: before directly inputting the pulse into the amplifier, a pulse stretcher is used to introduce a certain amount of dispersion into the ultra-short femtosecond (or picosecond) pulses output by the oscillator, thereby expanding the pulse width in the time domain by approximately one million times, reaching the picosecond or even nanosecond range. This not only significantly reduces the peak power but also ensures a safe limit of energy density per unit area. The pulse is then amplified in the amplifier, thereby reducing the risk of damage to related components and avoiding many adverse nonlinear effects such as gain saturation, which facilitates efficient energy storage in the gain medium. Once a sufficiently high energy level is achieved, a compressor is used to compensate for the dispersion, compressing the pulse width back to the femtosecond (or picosecond) level.

Figure 1. is from Arthur Ashkin、Gérard Mourou, and Donna Strickland's research results about chirped pulse amplification. They won the 2018 Nobel Prize due to their invention of the chirped pulse amplification technology

You can also click here and learn more about how chirped mirrors are used in chirped pulse amplification.

Dispersions for Femtosecond Lasers

Chromatic dispersion is a major concern for ultrafast pulsed lasers with pulse durations at the femtosecond level or less. Two important concepts are group delay dispersion (GDD) and third-order dispersion (TOD).

Group delay dispersion, also called second-order dispersion, if a pulse passes through a medium with non-zero GDD; components of different frequencies will propagate at different speeds, resulting in pulse broadening. GDD is the main cause of femtosecond pulse broadening.

Figure 2. The dotted line shows the GDD value of a femtoline low GDD mirror across the design wavelength range

Shalom EO - Manufacturer of Ultrafast Optics

Hangzhou Shalom EO offers various ultrafast optics and optics for femtosecond lasers. Off-the-shelf and custom femtosecond high reflection laser mirrors, ultrafast enhanced silver mirrors, chirped mirrors, double chirped mirror pairs, ultrafast harmonic separators, ultrafast thin lenses, ultrafast thin windows, ultrafast thin film polarizers, thin nonlinear bbo, lbo crystals for ultrafast lasers.

Related Articles

Tags: Learning About The Physics of Ultrafast Lasers